Duration 74′ –

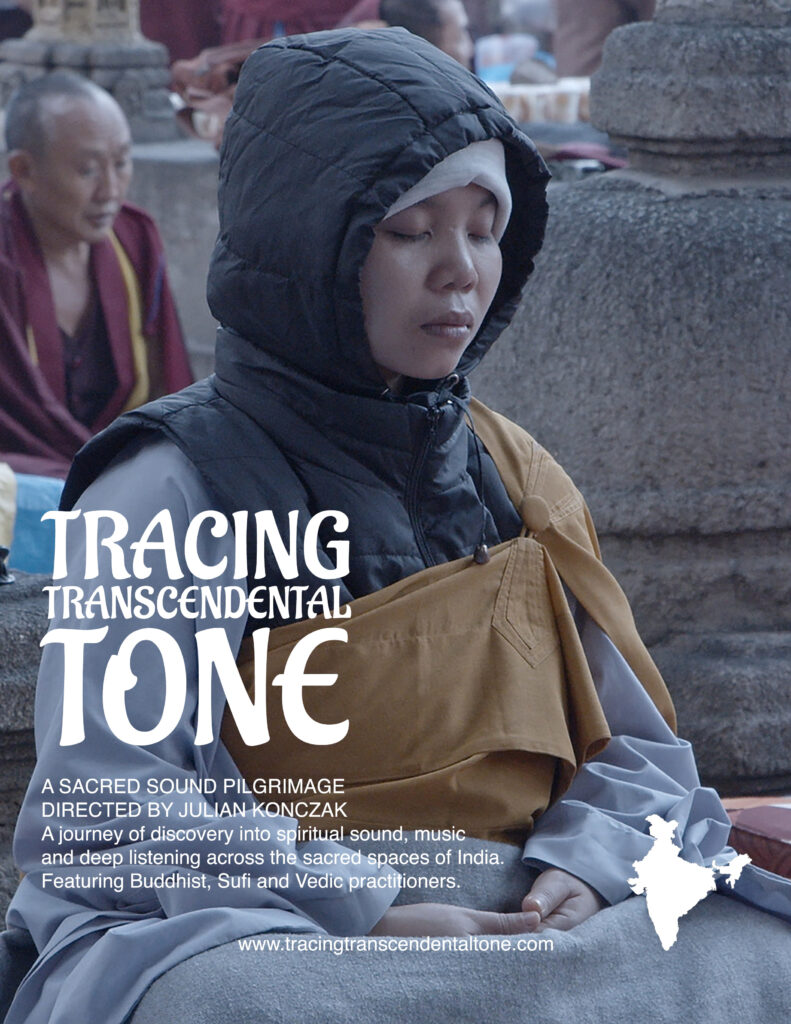

The multiple award-winning feature documentary follows a pilgrimage through the sacred sounds of India – a land of many faiths, including Vedanta, Islam and Buddhism. Using striking visual material accompanied by an evocative, multi-layered soundtrack, the audience is taken on a unique sonic journey through the sacred sound practices of many of the world’s key religions. A combination of interviews, performances, and natural sounds creates a rich, immersive cinematic experience. With an intimate, direct camera style, viewers can get close to the many spiritual practitioners, musicians, and meditation teachers who form the fabric of the journey. Bubbling hot springs, subtropical nocturnal symphonies of insects, and harsh, frozen mountain winds combine with mantra chanting, classical Hindustani music, and the dynamic temple sounds of drums and trumpets. This audiovisual tone poem invites you to experience greater sense awareness and the transformative and healing power of sound.

Watch the trailer:

The Q and A took place following a screening of the film at The Poly Falmouth on 21/01/2026

Tracing Transcendental Tone

Overview of Film Project (Abridged Version of Conference Paper)

The following words offer context for the feature documentary Tracing Transcendental Tone, providing insight into the personal, philosophical, metaphysical, and methodological processes that underpin its creation. Filmed during two field trips to India, the documentary was driven by heightened curiosity about the power of sound. Having, for the most part, collaborated with musicians on previous films and video installations, my focus shifted significantly from cinematography to audio. This transition enabled more effective engagement with immersive media, an area central to a recently completed PhD.

The project emerged from a convergence of artistic, spiritual, and philosophical interests. An expansion of my filmmaking practice led me to study and work with field recordist Chris Watson, an experience that developed an acoustic acuity and enabled a rediscovery of the sensory world—one that had previously been dominated by visual concerns. As a lifelong practitioner of contemplative traditions, I experienced a revelatory engagement with sound that coincided with an awareness of Nāda Yoga, a yogic tradition centred on meditating on inner sacred sound. As my focus deepened across these domains, it became imperative to locate the inquiry in India—the historical and philosophical seat of much of this exploration and a land profoundly shaped by sacred sound.

From its inception, the film was conceived as a work that offers a direct, experiential encounter. This aspiration toward immersion drew on the work of Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab and its commitment to embodied, contemplative viewing. While India offered enchanting material, it also presented logistical challenges. The project was undertaken in a spirit of independence: while seed funding supported the initial two-week expedition, the principal shooting took place outside formal funding structures and institutional expectations.

Tracing Transcendental Tone is fundamentally a sound film. Much of its production and post-production focused on evoking a vibratory and affective presence—one that could most faithfully represent the experience of immersion in a sound field of natural environments and ritual music, and ultimately invoke an altered state. Drawing on Jacques Derrida’s concept of the trace, sacred sound is understood as pointing beyond itself: a presence already marked by absence, a vibration that lingers beyond its point of origin. The aim is not to explain sacred traditions, but to evoke their atmospheres—to allow the listener to enter them through vibration.

Anahata: The Unstruck Sound

Nadis, Nāda Yoga, Rivers, Flow

The journey of making this work can be understood as following a flow. Before detailing the processes of actualisation, it is important to outline the metaphysical principles and states of being that made such an undertaking possible. The idea of tracing tone emerged early, informed by Dane Rudhyar’s The Magic of Tone and the Art of Music and Hazrat Inayat Khan’s The Mysticism of Sound, both of which address energetic forces underlying musical notes.

Central to this inquiry is the Eastern concept of nāda—a metaphysical principle suggesting that all life is interconnected through vibration. Sound, as it is heard, is intimately linked to the vibratory essence of the cosmos. Of particular significance is anāhata nāda, the “unstruck sound”: a transcendent vibration that has not yet materialised, experienced internally during deep meditation. It is a sound felt but not made, a presence without origin.

As Baird Hersey writes in The Practice of Nada Yoga: Meditation on the Inner Sacred Sound:

“Nad is a Sanskrit word which means to sound, thunder, roar, howl, or cry. Adding an ‘a’ at its end makes it nada, meaning sound or tone. Nada also means river or stream.”

Hersey describes levels of sound perception: Vaikhari (external sound), Madhyama (mental sound), Pashyanti (where sound and image converge), and Para, the transcendent realm of inner perception and connection.

These metaphysical abstractions find tangible form in nādis—subtle pranic channels within the body—which mirror the sacred rivers of India. The Ganges, Yamuna, and the mythic Saraswati are revered not only as rivers but also as vibrational currents woven into Vedic cosmology.

The film follows this sonic flow: from the rushing mountain streams of Ladakh, resonant with Buddhist chanting, to the muted currents of the Ganges at the ghats of Varanasi. Through this progression, the listener is invited into a state of sonic absorption and meditative attunement.

Etymological Roots

Trā / Tra / Trace

The title Tracing Transcendental Tone emerged early in the process, before significant filming had taken place. Though linguistically dense, it succinctly encapsulated the film’s ambition. As the work progressed and my engagement with Sanskrit deepened, the resonance of its alliterations became increasingly apparent.

The roots trā (long “aa”) and tra (short “a”) appear in both Sanskrit and Latin, revealing shared linguistic lineages associated with movement, passage, and transformation. In Sanskrit, trā appears in mantra, yantra, and tantra—each denoting a form of traversal or crossing. In Latin, tra- is found in words such as transcendence, traverse, transmutation, and trance, and similarly evokes liminality and transition.

These linguistic threads converge with Derrida’s concept of the trace: the lingering imprint of what is no longer fully present. Sacred sound operates within this register—a bell’s reverberation, a chant’s after-resonance, silence charged with memory. The film layers such sonic gestures as temporal inscriptions rather than static representations.

Even the recurring imagery of train travel reflects this logic. The rhythmic movement mirrors chant, creating a liminal state where movement and stillness coexist. The body synchronises with vibration, entering what neuroscientists describe as a transient state of hypofrontality—a meditative condition of heightened sensory awareness.

Here, trā serves as both a linguistic root and a conceptual compass, guiding the film’s exploration of how sacred sound enables crossings between time and timelessness, matter and spirit, self and other. The root becomes the route.

Silence

Deep Listening, Stillness, Meditation

Silence is a space of potency and absorption. The symbol OUM—composed of curves, a crescent, and a dot—maps states of consciousness: waking, dreaming, unconsciousness, illusion, and finally turiya, the silent, infinite ground. This silence is not empty; it is an active, fertile field containing the potential for all being.

Within Tracing Transcendental Tone, this understanding aligns with the work of composer and sonic theorist Pauline Oliveros and her Deep Listening practice. Influenced by Eastern philosophy, Oliveros advocated immersive, meditative listening—attending to the entire sound field, near and far, intentional and accidental.

Stillness is central here, for it is the realm of anāhata, the unstruck sound. The film draws on the contemplative temporal aesthetics of Nathaniel Dorsky and Andrei Tarkovsky, allowing breath, duration, and spaciousness to shape experience.

In the high plateaus of Ladakh, I spent days recording silence—soundscapes devoid of traffic and human intrusion. From this acoustic vantage point, subtle sounds—a lake touching its shore, individual snowflakes landing—heighten the perception of Tibetan Buddhist chants. The film offers listening as devotion and attention as an ethical and spiritual practice.

Sacred India

Religion and Music

India is a complex constellation of overlapping faiths, each shaped by language, region, ritual, and theology. Sacred sound occupies a radically different position in daily life, where awareness of divinity permeates the everyday.

Tracing Transcendental Tone does not seek to catalogue this vastness. Instead, it honours distinct sonic presences as pathways to the sacred. Featured traditions include Hindu devotional bhakti, Vedic chanting, Hindustani classical music and Dhrupad, Sufi Qawwali, Sikh Gurbani Kirtan, Tibetan Buddhist ritual chant, and South Indian Carnatic and temple music traditions.

Across these practices, sound functions as invocation, communion, and transformation—bridging human and transcendent realms.

Fieldwork

Methodology and Journal

The film was created outside formal production or research structures, enabling a hybrid methodology informed by sonic ethnography and phenomenology. A rigorous journaling practice accompanied the fieldwork, acting as a bridge between recording and spiritual inquiry, akin to Deborah Kapchan’s notion of “embodied ethnography.”

Listening became a way of knowing—aligned with Steven Feld’s concept of acoustemology. Ethical considerations of consent, reciprocity, and representation were continuously revisited; participants were collaborators rather than subjects. The film privileges non-intrusion, allowing rituals to unfold without staging.

As the journey progressed, the work took on the character of a pilgrimage. Encounters were often accidental, mediated by local guidance, chance meetings, and relational trust. Microphones, camera, body, and spirit were brought into resonance with sacred sound.

Structuring Experience

Recreating Revelation

Conceived as a meditative sound journey rather than a conventional documentary, the film’s editing functions as a sonic ritual. Drawing from chant and mantra, sounds cycle, overlap, and dissolve. The journey progresses from north to south, mirroring both the filming process and an experiential logic for the audience.

Rituals lasting hours or days were distilled into a cohesive sound world, inviting entrainment rather than explanation. Inspired by Tarkovsky’s “sculpting in time,” environmental recordings and ritual music are layered to create energetic continuity, punctuated by pauses that deepen presence.

The aim throughout is to invoke rather than interpret: to create a cinematic yantra—a vessel for resonance, attention, and transcendence.

Locations – India

Hazrat Nizamuddin Durga – Delhi

Hazrat Inayat Khan Durga – Delhi

Harmanndir Sahib – ‘The Golden Temple’ – Amritsar

Kathla Marta Temple – Dharamshala

Sahajayoga Ashram – Dharamshala

Tashita Tibetan Buddhist Retreat Centre – Daramkot

Dolma Ling Nunnery – Dharamshala

Nyoma Monastery – Ladakh

Tso Moriri – Ladakh

Shey Monastery – Ladakh

Parnath Niketan Ashram – Rishikesh

Panch Mandir Temple – Varanassi

Dwarika Dhish Mandir – Varanassi

Sri Lolarkeshwar Mahadev Temple – Varanasi

Sri Dakshinamurti Purvamnay Math – Varanasi

Mahabodhi Temple – Bodhgaya

Velloorkunnam Mahadeva Temple – Kerala

Chambra Mundachali Sree Vayanattu Kulavan Temple – Kerala

Thanks to

(in order of appearance)

Abiram Chaithanya

Jyoti Anand

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan

Sahil Bange

Jasdeep Kaur

Dilip Telang

Kavita Saxena

Lhundup Jamyang

Ram JI

Somnath Nirmal

Vivek Arya

Pavan Pandey

Further invaluable support from

Matthew Akester

Abhigya Shukla Akester

Ngawang Pelmo

www.mulberryleavesevents.com

http://kiranagharanamusicacademy.com/

Francis Johnson

Loic Ton-that

David Davenport-Firth

www.devotionmusic.org

Rajan Upadhyay

www.traditionalvaranasi.com

Akshi Yogshala

Katya Gunzinam

Skarma Gurmet

Caterina Capecchi

Trish Morris

Max Pugh

&

countless others who contributed to the creation of this work…

Antiquarian Images Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art

Post-Screening Q&A (Condensed Version) – 21/01/2026

Matthew Rogers:

Thank you for the film. It felt like a cinematic balm — an antidote to the poisonous political rhetoric of our times.

Julian Konczak:

Thank you. This film came from a feeling I’ve carried for many years. I’ve always been drawn to immersive spaces — places you can drop into. Even though this project uses other people’s sound, the editing was about holding a space, a visual and sonic world.

Matthew Rogers:

Your film foregrounds sound and tone rather than narrative. Was that intentional?

Julian Konczak:

Very much so. I didn’t start with theory, but I’m interested in what’s now called sensory cinema — the idea that cinema is an embodied experience and that narrative can be secondary. I wanted to make a film you could almost watch with your eyes closed.

Matthew Rogers:

How did you make the film in practical terms?

Julian Konczak:

The rulebook went out the window. I had no grant, little money, and no real support network. I travelled through India with sound equipment and a camera, responding organically to situations. People were incredibly generous — access came through conversation and trust rather than formal production structures.

Matthew Rogers:

The film avoids romanticising its subject. Was that deliberate?

Julian Konczak:

Yes. India is abrasive, overwhelming, and beautiful all at once. I wanted to include that friction rather than smooth it out. The beauty emerges through the difficulty.

Matthew Rogers:

There’s a strong sense of flow — almost a hypnotic quality.

Julian Konczak:

That’s central to my work. Long train journeys, ritual repetition, flicker — they induce altered states. I wanted the audience to experience that same entrainment.

Audience Question:

How did making the film change you?

Julian Konczak:

I thought I understood sacred sound before making it. The film showed me how little I knew. Afterwards, I studied Indian music and Sanskrit, and began a daily practice. The film opened a door I’m still walking through.